Since 2013 the number of opioid prescriptions written by doctors has gone down dramatically (see Chart #1 at bottom of this article for 2013–2016 prescription rates). Overall, prescriptions have dropped 14.6% in the United States in the 2013–2016 period. At the same time, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reports that overdose deaths are climbing exponentially, driven principally by illegal drugs such as heroin and fentanyl.

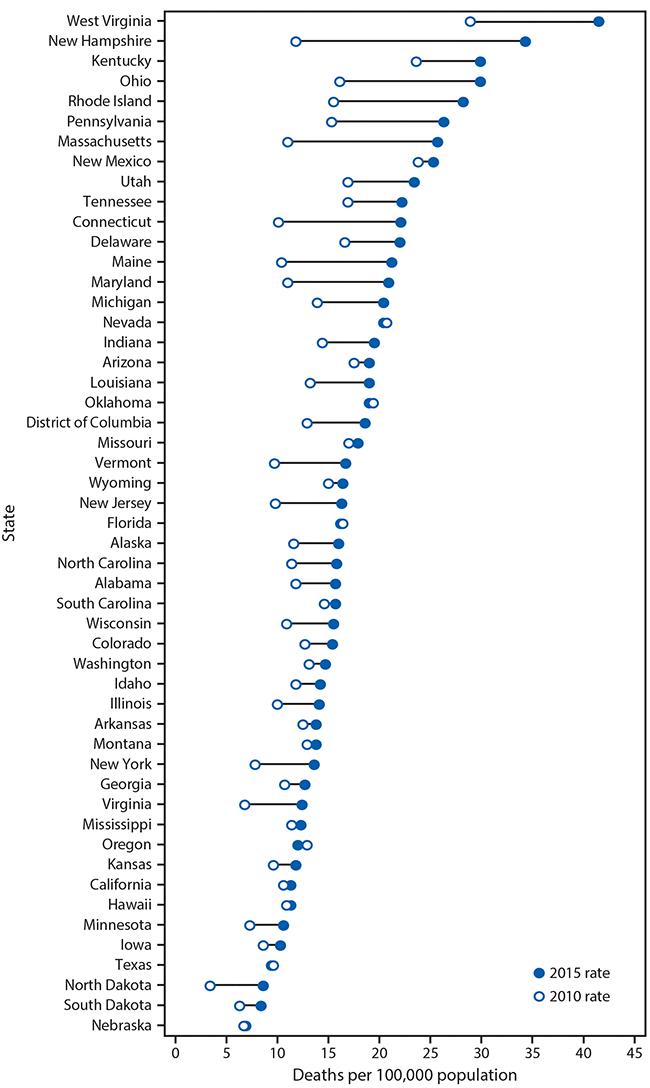

Certain states have seen much larger reductions in prescriptions than the national average of 14.6% including West Virginia (27.6%), Massachusetts (22.5%), New Hampshire (21.3%), Ohio (19.6%), Kentucky (16.4%) and Pennsylvania (16.2%). Yet it is these states that lead the nation in overdose deaths (See CDC Chart #2 at the bottom of this article).

The most popular narrative is that legal opioid prescriptions – over-marketed and indiscriminately prescribed – were the gateway to the illegal street drugs and thus the manufacturers and dispensers of legal opioids should be held accountable. Currently, there are hundreds of lawsuits, most of which have been consolidated in a Federal Court in Cleveland, all directed at the manufacturers of drugs such as oxycodone.

United States Attorney General Jeff Sessions has recently announced that the Federal Government will join in such lawsuits which have been filed by numerous states and localities. In some of these cases, doctors who dispensed legal opioids are being caught up as defendants in these lawsuits. This is particularly troublesome for “pain management” physicians.

The CDC promulgated guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. The CDC Guidelines indicate that “non-pharmacologic therapy and non-opioid therapy are preferred for chronic pain”. When opioids are used for acute pain, “clinicians should prescribe the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids and three days or less will often be sufficient; more than seven days will rarely be needed.”

The CDC encourages doctors to use the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) in their state as well as to conduct urine testing before starting the opioid therapy for chronic pain.

The CDC Guidelines have been mimicked by state legislatures in enacting state laws but these often become not “guidelines” but strict rules used by payers to deny reimbursement for opioids which are entirely appropriate. The CDC Guidelines recognize that there are clinical situations where a 3 day/7 day guideline is not appropriate.

The most typical limitation on opioid prescribing in that doctors may only write a prescription for seven days. Such a law may appear sensible until one realizes that the patient may want to go to other places (the street) rather than having to make a doctor’s visit every week.

While many states that have enacted the seven day limit, those states have also provided for thoughtful exceptions where medically indicated such as for patients with chronic pain. The most recent seven day enactment occurred in early March in Florida which, inexplicably, applied the seven day rule with certain exceptions but not others. For example, a patient who received a hip replacement would have to return to the doctor for a new prescription after seven days. That approach may drive patients away from doctor offices to other sources. This inconsistency in application of the CDC recommendation only creates confusion on the front lines of the epidemic.

However, it appears that the most popular narrative may not be correct with the result that the “cures” being legislated may not be correct either. Sally Satel, M.D. is an addiction psychiatrist who wrote an article entitled “The Myth of What’s Driving the Opioid Crisis”.

Dr. Satel’s principal point is that, while there may have been an over prescribing of prescription drugs, the main reason for the spike in overdose deaths comes not from doctors’ prescriptions but, rather, from a diversion of prescribed drugs by the patients and from street drugs such as heroin and fentanyl.

Dr. Satel notes that most legislative and regulatory “fixes” rely on the “supply side” of the opioid epidemic (telling doctors not to prescribe) rather than on the “demand side” of the epidemic.

On the “demand side,” two things that can be done are making better use of anti-addiction medications and building a better addiction treatment infrastructure. Methadone and buprenorphine are opioid medications for treating addictions that can be prescribed in order to wean patients of opioids and to maintain stability. Another medication, naltrexone, prevents a patient who tries heroin from experiencing any effects. When these medicines are combined with cognitive behavioral therapy there is a good chance of recovery.

In short, an agenda to address the opioid epidemic, which is heavily weighted toward pill control, is not enough and the “demand side” is equally important and is generally being ignored. Moreover, the campaign against opioids results in doctors not prescribing opioids even when they are what is needed.

Perhaps a more complete narrative would recognize the socioeconomic dimensions of the opioid “epidemic.” Certain states have experienced no epidemic while others have truly experienced a marked increase in overdose deaths. Look at the CDC chart (Chart #2) below and compare the “no real” epidemic states with the “real” epidemic states. Why do Florida, Texas and Nebraska not show any appreciable increase in overdose deaths from 2010 to 2015 while there is a massive increase in West Virginia, New Hampshire, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts?

The state data contained in Chart #1 and Chart #2 below raises additional arguments against the popular narrative. For example, New Hampshire, Massachusetts Connecticut and Rhode Island are “epidemic” states (Chart #2) in that opioid overdose deaths have increased markedly in the 2010-15 time period, but, in each instance, the number of opioid prescriptions are less than the national average (Chart #1).

Meanwhile Montana, Arkansas, Mississippi, Nevada, Oklahoma and Missouri have an above average number of opioid prescriptions (Chart #1) but are not “epidemic” states (Chart #2) in that overdose deaths have not appreciably increased in the 2010–15 time period.

The bottom line: the most current explanation is full of holes, and lacks creative solutions that would work for all patients. Our current “fixes” are driven by an explanation that is woefully incomplete and will likely not stem the current epidemic.

Chart #1

Chart #2

Age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths, by state — 2010 and 2015

1211 Cathedral Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201

1211 Cathedral Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 – Call Our Offices – 443.449.2287