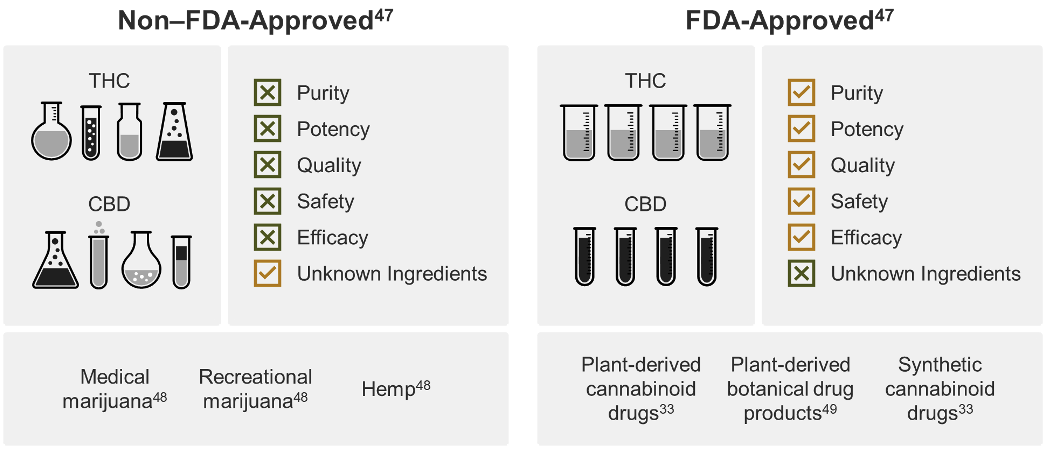

There are only four FDA-approved cannabis-based medicines that meet the U.S. Food & Drug Administration’s (FDA) standards for efficacy, safety, and quality. In 2018, FDA approved Epidiolex, a botanically derived cannabidiol (CBD) human drug product. Marinol (1985), Cesamet (1985), and Syndros (2016) are FDA-approved human drug products that are synthetic forms of delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (delta-9 THC).All other cannabis products, including those sold in state medical and recreational programs, are not reviewed or approved by the FDA. Inconsistent quality control standards in state programs as well as a paucity of robust clinical evidence on the safety and efficacy on non-FDA-approved cannabis products present challenges for physicians and their management of patients’ interest in using cannabis.

Below is a detailed explanation of the current regulatory environment with respect to cannabis in the United States that can serve as a valuable resource for physicians.

Joseph A. Schwartz, III

President, PRI

We need to talk…about cannabis.

With conflicting regulations, widespread misinformation, and a lack of high-quality clinical evidence, it is difficult for health care providers to access the tools needed to accurately inform and manage patients about cannabis.The information provided below can help you understand the science of cannabinoids, its relation to medicine, and how these current landscapes impact the medical community.

Key points

- The terms around cannabis and cannabis products are varied and confusing and depend on whether references to the terminology is colloquial, legal, commercial, or scientific.

- Cannabis is a complex plant that contains over 500 compounds – it is more than cannabidiol (CBD) or tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).

- The 2018 Farm Bill removed hemp (derivatives of cannabis with ≤ 0.3% delta-9 THC by dry weight) from the federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA) definition of marijuana (thereby descheduling those formulations and removing them from U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration jurisdiction), resulting in an explosion of hemp consumer products. However, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) maintains its authority over products containing cannabis and its components and cannabis formulations with > 0.3% delta-9 THC by dry weight remain schedule I controlled substances under the CSA.

- There are only 4 FDA-approved cannabis-derived or synthetic cannabinoid products that meet FDA standards for safety, efficacy, and quality. Non‒FDA-approved cannabis and cannabis-derived products are regulated under a patchwork of state regulation, evidentiary, and quality standards.

- The absence of rigorous safety and efficacy evidence supporting the therapeutic use of non-FDA-approved cannabinoid products and unreliable quality in non-FDA approved cannabis products present challenges for physicians and risks for patients.

- This ever-changing landscape has created uncertainty within the medical community regarding best practices for patients using non-FDA-approved cannabis and cannabis-derived products.

- Several medical societies released statements regarding their concerns about the lack of research supporting the use of cannabis and cannabis-derived products.

Cannabis, what’s in a name?

- Cannabis and cannabis-derived products are defined differently depending on speaker and content. Cannabis is the common name for the plant Cannabis sativa L.1 Under the CSA, cannabis is treated as either hemp (contains ≤ 0.3% delta-9 THC by dry weight) or marijuana (contains > 0.3% delta-9 THC by dry weight.)2 Cannabis products may use marketing terms that do not have accepted scientific, legal, or regulatory definitions such as broad spectrum, hemp/hempseed oil, isolate, and medical or recreational cannabis/marijuana.1, 3, 4 It should be noted that medical and recreational cannabis only differ in intent of use.4 Recreational cannabis is sometimes called adult-use cannabis. Medical cannabis is sold to a consumer after they receive a recommendation by a health care provider who certifies that the patient suffers from a condition deemed qualifying by the laws of their state.5

Defining cannabis in scientific terms has also led to points of disagreement. It was once thought that cannabis had subspecies, such as “sativa” or “indica,” which indicate its potency and expected outcome (for example, uplifting or sedating).1, 6 Botanical science indicates that cannabis is a single species genus, Cannabis sativa L.1 It can be bred to create varying cannabinoid concentrations, but you cannot look at a plant and determine its cannabinoid content.1, 6 Appropriate assays are required.7

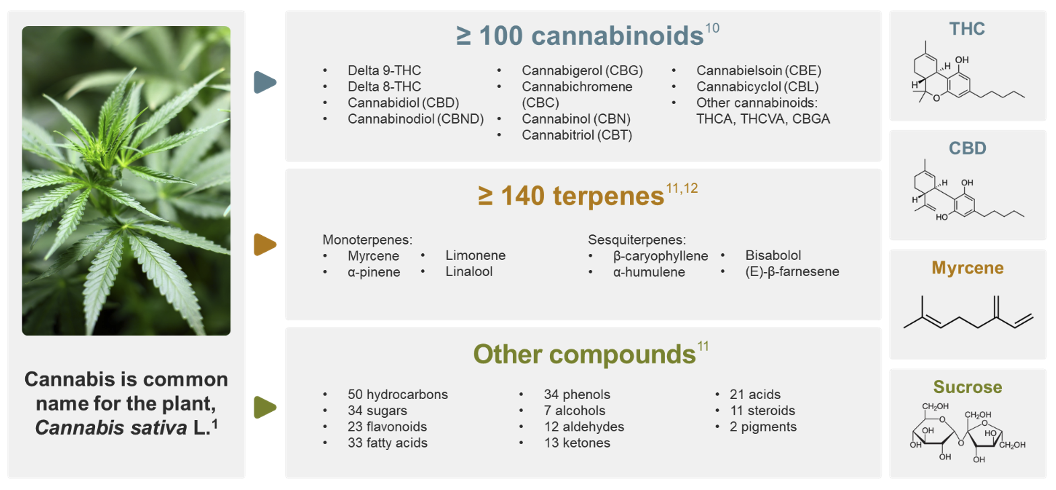

If you do an internet search you may find questions asking whether CBD, THC, and cannabis are the same thing. One consumer report found that nearly 4 in 10 consumers thought that CBD was another name for marijuana.8 In fact, CBD and THC are examples of one type of molecule found in the cannabis plant called phytocannabinoids.9 However, like many plants, cannabis is very complex and contains much more than just CBD and THC.10

Cannabis status: it’s complicated.

Cannabis sativa L is a complex botanical mixture. Over 500 compounds are found in cannabis, including numerous phytocannabinoids, terpenes, and other biologically active compounds.10-12

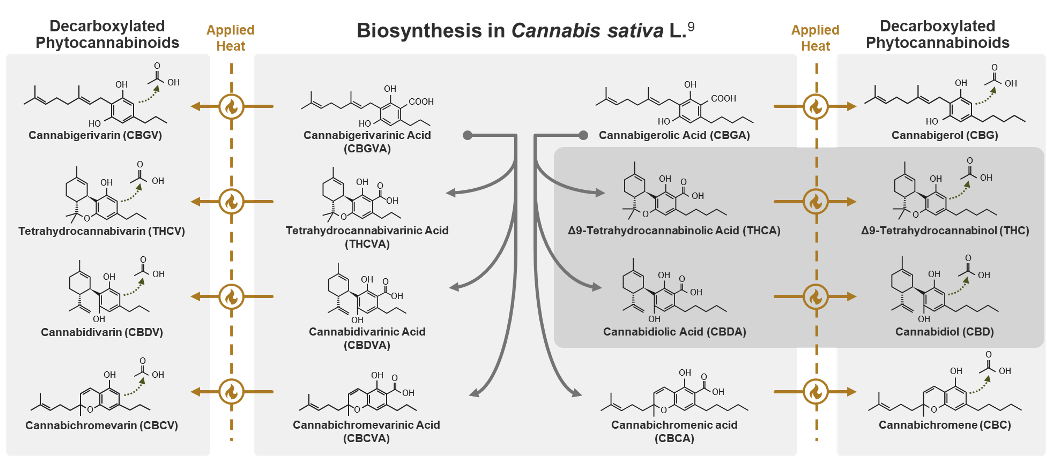

While phytocannabinoids are defined as being produced by cannabis, some of their active forms are not directly synthesized by the cannabis plant.9 For example, while CBD and THC are naturally produced in very low levels, usable quantities are formed by decarboxylation, a process where heat helps remove a carboxylic acid group from their precursor molecules cannabidiolic acid (CBDA) and tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA). Over time or with additional heat, even more active and inactive metabolites may be created. Due to this instability and the number of phytocannabinoids in the cannabis plant, it can be difficult to fully distinguish an individual molecule’s role in therapeutic effects.11

Phytocannabinoid instability is important because their levels and ratios can determine the physiologic effects of cannabis.7, 13 In one study, the amount of THC ranged from 0.3% to 20.8% due to genetic variation.14 Changes in humidity, temperature, radiation, soil nutrients, and parasites can also strongly influence cannabinoid content.15 A 2009 study showed that cannabis grown in cooler months generated a crop-yield and cannabinoid potency that were a quarter of plants grown in warmer months.16 Additional environmental impact results from soil contents as cannabis is an efficient bioaccumulator.17-19 The cannabis plant can accumulate pesticides, heavy metals, radioactive compounds, hydrocarbons, and other chemical solvents.20 Cannabis is so effective at removing contaminants that in 1986 it was used to decrease radiation levels in the soil after the Chernobyl disaster. As a result of these internal and external factors, cannabinoid content in botanical material is unpredictable. This unpredictability is compounded by the varying extraction and manufacturing methods used, which also impact the finished product cannabinoid content.7 These factors highlight why the lack of consistent regulation, quality control oversight, and standardized laboratory testing can impact patient safety.

Patchwork of regulation for cannabis and cannabis-derived products

- The regulation of cannabis has changed rapidly within the last 30 years.21-26 The biggest change in federal cannabis regulation occurred when the 2018 Agricultural Improvement Act (also known as the Farm Bill) removed cannabis and its derivatives with ≤ 0.3% delta-9 THC by dry weight from the definition of marijuana and from schedule I in the Controlled Substance Ac (cannabis preparations containing > 0.3% delta-9 THC by dry weight remain schedule I controlled substances)t.26, 27 However, while hemp was no longer considered a controlled substance, the FDA retains authority over products containing hemp and its components under the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act).24, 26

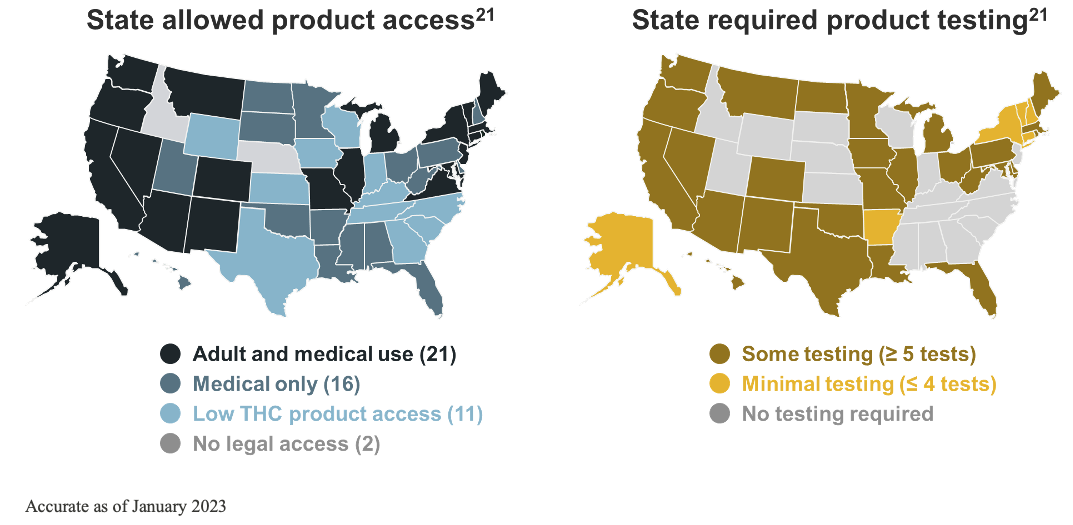

It is at the state level where most of the change has taken place as individual states have enacted various laws to allow legal access to cannabis for medical use and/or recreational marijuana. In 1996, Californian voters approved Proposition 215, making it the first state to pass a medical marijuana initiative.21 By 2012, Colorado and Washington had legalized recreational marijuana. Utah became the first state to pass a CBD access law in 2014. By the 2020s, all but 2 states have allowed some access to cannabis or cannabis-derived products.21, 28

Regardless of these state laws, it is still federally illegal to manufacture, dispense, prescribe, or possess marijuana (cannabis preparations containing > 0.3 % delta-9 THC by dry weight), which remains a schedule I substance under the federal CSA.24 It is also illegal under the federal FD&C Act to sell food or supplements containing CBD or THC as both CBD and THC were studied as drugs before they were marketed as foods or supplements. As former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb stated, “[FDA will] take enforcement action needed to protect public health against companies illegally selling cannabis and cannabis-derived products that can put consumers at risk and are being marketed in violation of the FDA’s authorities.” Between 2015 – 2022, the FDA issued over 110 warning letters to producers of unregulated cannabis-derived products for unsubstantiated medical claims.29 The United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) also retain legal authority over marijuana under the Controlled Substances Act since it is still a Schedule I controlled substance.27, 30

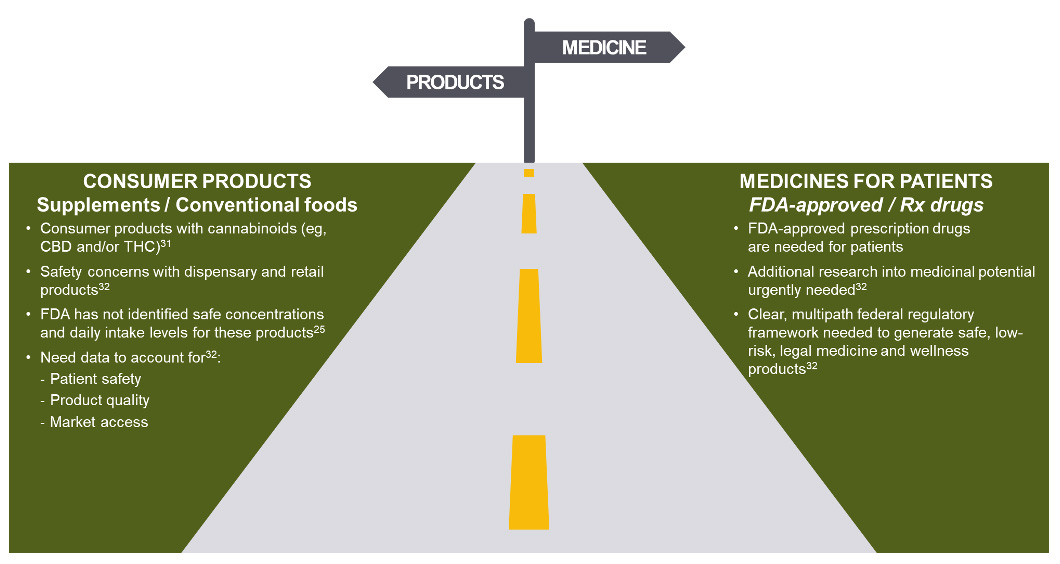

On January 26, 2023, the FDA announced that it believes a new regulatory pathway is needed for CBD products to be lawfully marketed in the United States, one which balances the public’s desire for access to CBD and the regulatory oversight required to manage risks.25 In the statement, the FDA noted that they do not intend to pursue rulemaking allowing the use of CBD in dietary supplements or conventional foods and that they will continue to take action against cannabis-derived products in their role as protectors of public health and safety.31, 32

The FDA has stated that products containing cannabis or cannabis-derived compounds will be treated the same as any other FDA-regulated products — meaning they’re subject to the same authorities and requirements as FDA-regulated products containing any other substance.33 FDA has also said the agency’s drug approval process represents the best way to help ensure that safe and effective new medicines, including any drugs derived from cannabis, are available to patients in need of appropriate medical therapy. FDA stands ready to work with companies interested in bringing safe, effective, and quality products to market through the drug approval process.

Are cannabis and cannabinoid drugs FDA approved?

The FDA-approval pathway ensures purity, consistency, and stability of cannabis based drugs and holds companies accountable to provide unbiased, substantial evidence of their drug’s efficacy and safety profiles. In a drug development program, multiple clinical trials provide detailed prescribing information, including dosing and safety data.34, 35 This process is critical as there will always be benefits and risks from a drug.36 With this information, a health care provider can manage dosing and mitigate any potential risks for their patients when prescribing the drug.

Development of a medicine from the cannabis plant is complex. The same active pharmaceutical ingredient but in a different formulation or delivery method can impact the final safety and efficacy of the drug. As with any drug substance, the route of administration will affect the active ingredient pharmacokinetics.37-39 Cannabinoids have poor solubility in water, thus various solutes are used and will change the bioavailability of the active pharmaceutical ingredient.40 Even in the processing and packaging of a drug, issues with stability and degradation of cannabis compounds must be considered.40, 41

As of July 2023, there are 4 cannabis or cannabinoid-based drugs that have been successfully approved by the FDA:

- 1 CBD product for the treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, Dravet syndrome, and tuberous sclerosis complex in patients 1 year and older.42

- 2 synthetic delta-9-THC products for treating nausea with chemotherapy and anorexia associated with weight loss in AIDS patients.43, 44

- 1 synthetic product with a similar structure to THC for treating patients with nausea associated with chemotherapy.45

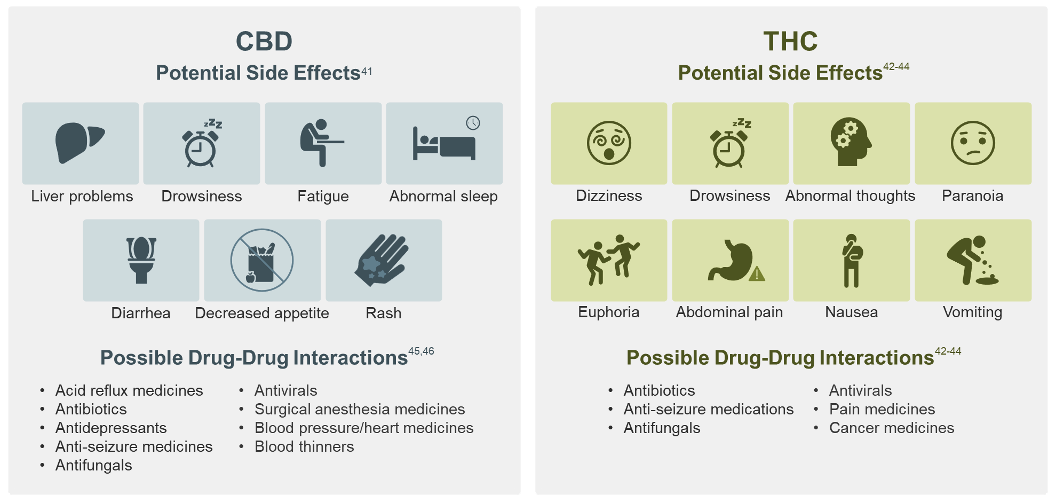

Based on the 4 FDA-approved CBD or THC drugs, CBD and THC may have the following side effects and drug-drug interactions in the conditions studied:46, 47

This is a general list of possible interactions with these types of medication; it is not a complete list of all potential side effects or drug interactions.

When it comes to the FDA-approved formulations of THC, the FDA recommends a starting dose of 2.5 mg.44 It was noted within those clinical trials that some patients experienced euphoria at this starting dose. Because these doses are regulated, health care providers will know the exact amounts of THC given to their patients. Unfortunately, this may not be applicable to non–FDA-approved cannabis and cannabis-derived products.48-50

Current state of non‒FDA-approved cannabis and derived products

Non‒FDA-approved cannabis and cannabis-derived products exist under a patchwork of regulation, dependent on individual state policy to establish and enforce quality standards.21 All but 2 states allow access to cannabis and cannabis-derived products, yet, despite this robust access, there is a lack of consistent testing requirements.7, 21

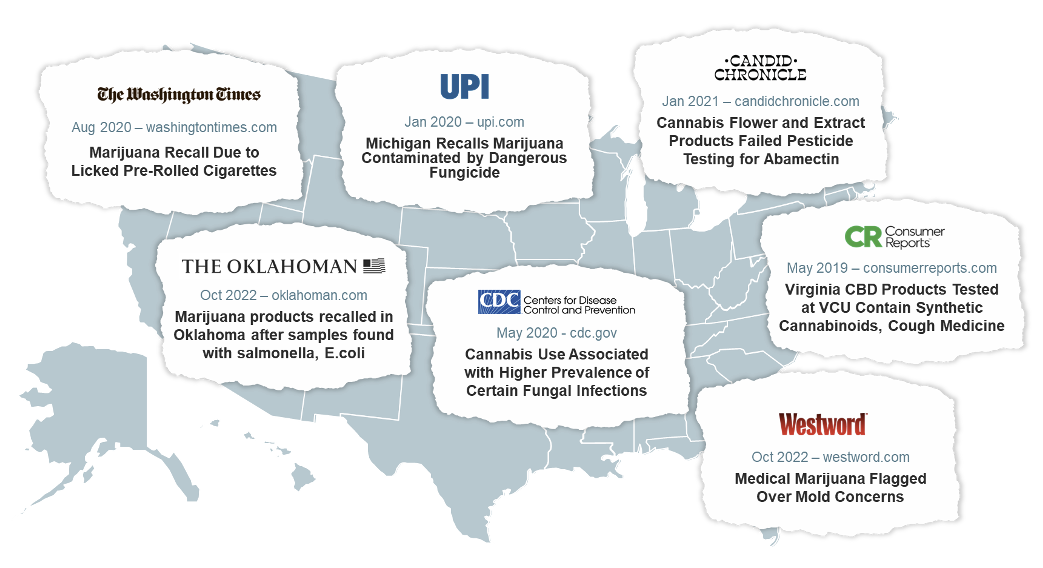

Remember that cannabis is a highly efficient bioaccumulator.17-19 So, testing needs to be performed on cannabis-derived products to ensure they are free from things like fungal contamination, heavy metals, microbes, pesticides, and impurities.7 However, the lack of consistent manufacturing standards and testing can and has resulted in inconsistent and contaminated products on the market.29, 51-59

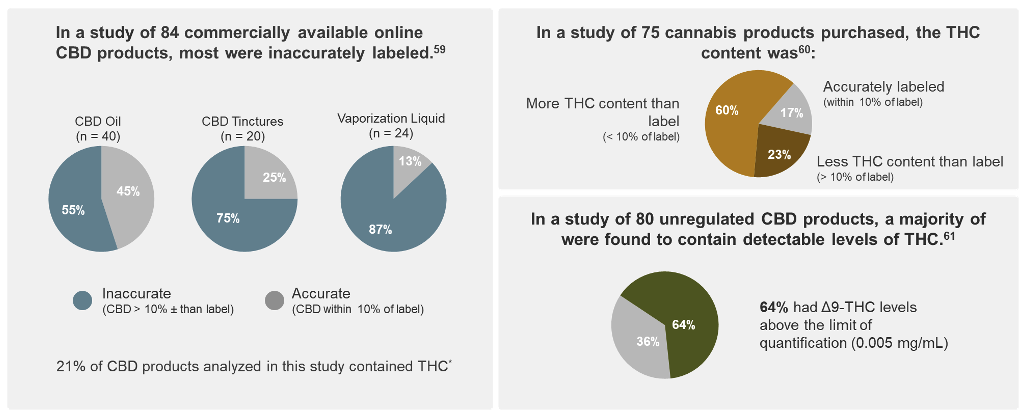

Potency tests should also be performed to ensure the identity and quantity of cannabinoids match what is stated on the label.7 Several studies have found inaccuracies in commercial products, including hemp-derived and those for medical marijuana use, such as THC content much higher than what was on the product label.60-62

*Cannabinoid products from 31 companies were purchased and analyzed for CBD content by high-performance liquid chromatography.

A need for education and evidence from the medical community

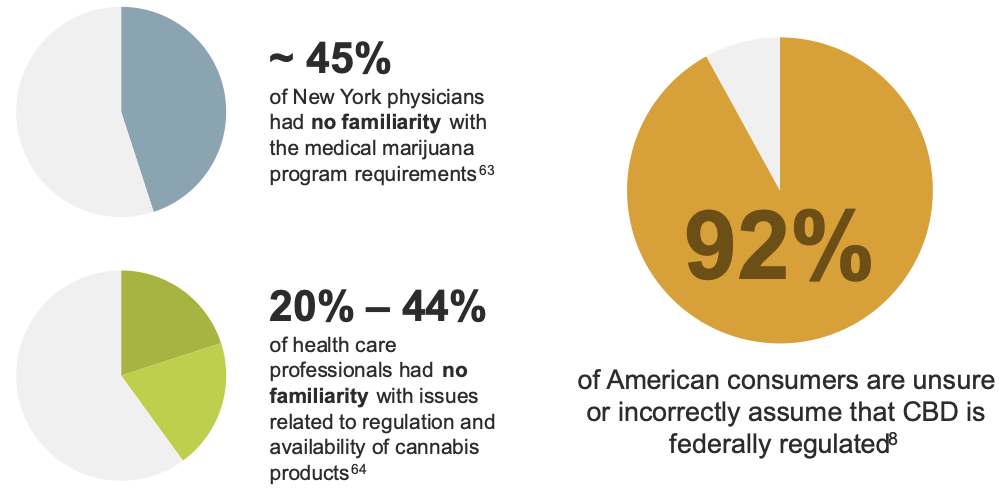

This ever-changing landscape has created uncertainty within the medical community regarding best practices for patients using cannabis and cannabis-derived products.8, 63, 64 There have been several studies that found that both the public and health care providers have misconceptions over how cannabis and cannabis-derived products are regulated and accessed.

Several medical societies have released statements regarding their concerns about the lack of research supporting the use of cannabis and cannabis-derived products in treating various disease states.

A statement released by the American Academy of Family Physicians, while recognizing the public support for medical marijuana and cannabinoids advocated that usage be based on high-quality, evidence-based public health, policy, and patient-centered research, including the impact on vulnerable populations.65 The group concluded, “Utilizing an interdisciplinary, evidence-based approach to addressing both medical and recreational marijuana and cannabis use is essential to promote public health, inform policy, and provide patient-centered care.” The group also mentioned that approximately 9% of people develop a marijuana addiction, which may vary by age of first use and frequency of use. They also stated that marijuana has been linked to accelerating the trajectory of schizophrenia and psychoses, particularly in people that have pre-existing genetic indicators.

“Existing limited medical research does not support the present and proposed legislative policies across the country that promote cannabis-based products as treatment options for the majority of neurologic disorders,” said the American Academy of Neurology.66

“Studies… show an association between cannabis use and increased rates of non-medical opioid use…,” said the American Society of Addiction Medicine.67 The policy statement included reports of significant increases in cannabis vaping in US middle and high school students. The group also stated that cannabis use was associated with psychosis, psychiatric comorbidity, and cannabis use disorder (CUD) was associated with disability. “Evidence-informed substance use prevention and treatment interventions can avert or delay the initiation of cannabis use, stop the progression from use to harmful use or addiction, and reduce cannabis use-related negative health, social, and economic impacts…. An evidence-based approach to treatment can mitigate CUD-related harm.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics published a statement saying that the AAP “opposes “medical marijuana” outside the regulatory process of the US Food and Drug Administration.68 . The AAP strongly supports research and development of pharmaceutical cannabinoids and supports a review of policies promoting research on the medical use of these compounds.

The American Psychiatric Association released a statement saying that they could not endorse the use of medical cannabis due to “…the lack of any credible studies demonstrating clinical effectiveness….69There is great variability in the form, dose and potency of cannabis. Furthermore, there are numerous other compounds in products marketed as cannabidiol or cannabis with unknown health effects.”

“Although cannabis and cannabis derived products are becoming increasingly available in the United States, there is very little scientific evidence regarding their safety and effectiveness,” according to the Alzheimer’s Association.70

In summation, while there is a clear interest in using cannabis-derived products, the evidence is not currently to the rigorous standards that we would expect from any other drug, and the agencies and associations who support the public and health care providers are concerned. While we all want to find therapies for patients with unmet needs, cannabis should not get a pass on the system of regulation that has served public health and safety for decades.

Where are we now?

Understanding cannabis using evidence-based information will help the medical community develop solutions to mitigate harmful effects of cumulative exposure to unregulated cannabis-derived products. As more cannabis research is performed and new products develop, we must clearly differentiate between FDA-approved drugs and cannabinoid-based consumer goods Therefore, we need to encourage the development of more FDA-approved cannabinoid-based medications. Hopefully, through rigorous research, consistent testing, and FDA oversight a system could be established to ensure that cannabis and cannabis-derived products can be used safely and effectively, under medical professional oversight that will ensure appropriate dosing and mitigate any risks.

References

1. Small E. Evolution and Classification of Cannabis sativa (Marijuana, Hemp) in Relation to Human Utilization. The Botanical Review. Sept 1 2015;81(3):189-294. doi:10.1007/s12229-015-9157-3

2. Establishment of a Domestic Hemp Production Program, Department of Agriculture (USDA) 7 CFR §990 (2021). Accessed 3 Dec 2021. Link

3. Gresoski K. Types of CBD: Full Spectrum vs Broad Spectrum vs Isolate. Hempsley. 2019. Accessed Jan 19, 2022. https://hempsley.com/blogs/science/types-of-cbd-full-spectrum-vs-broad-spectrum-vs-isolate

4. Bostwick JM. Blurred boundaries: the therapeutics and politics of medical marijuana. Mayo Clin Proc. Feb 2012;87(2):172-86. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.10.003

5. Gregorio J. Physicians, medical marijuana, and the law. Virtual Mentor. Sep 1 2014;16(9):732-8. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2014.16.09.hlaw1-1409

6. McPartland JM. Cannabis Systematics at the Levels of Family, Genus, and Species. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2018;3(1):203-212. doi:10.1089/can.2018.0039

7. Sarma ND, Waye A, ElSohly MA, et al. Cannabis Inflorescence for Medical Purposes: USP Considerations for Quality Attributes. J Nat Prod. Apr 24 2020;83(4):1334-1351. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b01200

8. Consumer Brands Association. The Urgent Need for CBD Clarity. Accessed May 19, 2020. https://consumerbrandsassociation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/ConsumerBrands_CBD_Clarity.pdf

9. Noestheden M, Friedlander G, Anspach J, Krepich S, Hyland KC, Zandberg WF. Chromatographic characterisation of 11 phytocannabinoids: Quantitative and fit-to-purpose performance as a function of extra-column variance. Phytochem Anal. Sep 2018;29(5):507-515. doi:10.1002/pca.2761

10. ElSohly M, Gul W. Constituents of Cannabis sativa. In: Pertwee R, ed. Handbook of Cannabis. Oxford University Press; 2014:3-22:chap 1.

11. Brenneisen R. Chemistry and Analysis of Phytocannabinoids and Other Cannabis Constituents. In: ElSohly MA, ed. Marijuana and the Cannabinoids. Humana Press; 2007:17-49:chap Chapter 2. Forensic Science And Medicine.

12. Booth JK, Bohlmann J. Terpenes in Cannabis sativa – From plant genome to humans. Plant Sci. Jul 2019;284:67-72. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.03.022

13. de la Fuente A, Zamberlan F, Sanchez Ferran A, Carrillo F, Tagliazucchi E, Pallavicini C. Relationship among subjective responses, flavor, and chemical composition across more than 800 commercial cannabis varieties. J Cannabis Res. Jul 17 2020;2(1):21. doi:10.1186/s42238-020-00028-y

14. Fischedick JT, Hazekamp A, Erkelens T, Choi YH, Verpoorte R. Metabolic fingerprinting of Cannabis sativa L., cannabinoids and terpenoids for chemotaxonomic and drug standardization purposes. Phytochemistry. Dec 2010;71(17-18):2058-73. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.10.001

15. Micalizzi G, Vento F, Alibrando F, Donnarumma D, Dugo P, Mondello L. Cannabis Sativa L.: a comprehensive review on the analytical methodologies for cannabinoids and terpenes characterization. J Chromatogr A. Jan 25 2021;1637:461864. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2020.461864

16. Potter D. The Propagation Characterisation and Optimisation of Cannabis Sativa L as a Phytopharmaceutical. King’s College London; 2009.

17. Flores RM. Co-Produced Water Management and Environmental Impacts. In: Flores RM, ed. Coal and Coalbed Gas. Elsevier; 2014:437-508.

18. Husain R, Weeden H, Bogush D, et al. Enhanced tolerance of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) plants on abandoned mine land soil leads to overexpression of cannabinoids. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0221570. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0221570

19. Newman MC. Bioaccumulation from food and trophic transfer. Fundamentals of Ecotoxicology. CRC Press; 2019:157-180.

20. Rheay HT, Omondi EC, Brewer CE. Potential of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) for paired phytoremediation and bioenergy production. GCB Bioenergy. 2020;13(4):525-536. doi:10.1111/gcbb.12782

21. ProCon.org. Legal Medical Marijuana States and DC. Updated Jun. 2021. https://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/legal-medical-marijuana-states-and-dc/

22. Little B. Why the US Made Marijuana Illegal. History. 2018. Accessed Jul 6, 2021. https://www.history.com/news/why-the-u-s-made-marijuana-illegal

23. Statement of Principles on Industrial Hemp, Department of Agriculture (USDA) 81 FR §53395 (2016). https://thefederalregister.org/81-FR/53395

24. Gottlieb S. Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on signing of the Agriculture Improvement Act and the agency’s regulation of products containing cannabis and cannabis-derived compounds. 2018. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-signing-agriculture-improvement-act-and-agencys

25. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA Concludes that Existing Regulatory Frameworks for Foods and Supplements are Not Appropriate for Cannabidiol, Will Work with Congress on a New Way Forward. Updated Jan 1, 2023. 2023. Accessed Feb 10, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-concludes-existing-regulatory-frameworks-foods-and-supplements-are-not-appropriate-cannabidiol

26. US Food and Drug Administration. Hemp Production and the 2018 Farm Bill. 2019. Accessed Dec 2, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/congressional-testimony/hemp-production-and-2018-farm-bill-07252019

27. US Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug Scheduling. Accessed Dec 4, 2021. https://www.dea.gov/drug-information/drug-scheduling

28. State of Utah. H.B. 105 Plant Extract Amendments. 2014. Accessed Feb 10, 2023. https://le.utah.gov/~2014/bills/static/HB0105.html

29. US Food and Drug Administration. Warning Letters and Test Results for Cannabidiol-Related Products. FDA.gov. Updated May 6 2022. 2022. Accessed Sep 1, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/warning-letters-and-test-results-cannabidiol-related-products

30. Justice/DEA Do. (2020) Marijuana/Cannabis.

31. Marcu J. The legalization of cannabinoid products and standardizing cannabis-drug development in the United States: a brief report. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. Sep 2020;22(3):289-293. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.3/jmarcu

32. Ciolino LA, Ranieri TL, Taylor AM. Commercial cannabis consumer products part 1: GC-MS qualitative analysis of cannabis cannabinoids. Forensic Sci Int. Aug 2018;289:429-437. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2018.05.032

33. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Regulation of Cannabis and Cannabis-Derived Products, Including Cannabidiol (CBD). Updated Jul 5, 2023. 2023. Accessed Jul 13, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-regulation-cannabis-and-cannabis-derived-products-including-cannabidiol-cbd

34. US Food and Drug Administration. Is It Really ‘FDA Approved?’. Updated Jan 17. 2017. Accessed Sept 2, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/it-really-fda-approved

35. US Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing Information Resources. Updated Jan 19, 2023. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/fdas-labeling-resources-human-prescription-drugs/prescribing-information-resources

36. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Development & Approval Process | Drugs. 2021. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs

37. de Kruijf W, Ehrhardt C. Inhalation delivery of complex drugs-the next steps. Curr Opin Pharmacol. Oct 2017;36:52-57. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2017.07.015

38. Lalan M, Tandel H, Lalani R, Patel V, Misra A. Inhalation Drug Therapy: Emerging Trends in Nasal and Pulmonary Drug Delivery. In: Misra A, Shahiwala A, eds. Novel Drug Delivery Technologies. Springer Singapore; 2019:291-333:chap Chapter 9.

39. Seifert R. Basic Knowledge of Pharmacology. Springer International Publishing; 2019.

40. Citti C, Braghiroli D, Vandelli MA, Cannazza G. Pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis of cannabinoids: A critical review. J Pharm Biomed Anal. Jan 5 2018;147:565-579. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2017.06.003

41. Stella B, Baratta F, Della Pepa C, Arpicco S, Gastaldi D, Dosio F. Cannabinoid Formulations and Delivery Systems: Current and Future Options to Treat Pain. Drugs. Sep 2021;81(13):1513-1557. doi:10.1007/s40265-021-01579-x

42. Epidiolex® (cannabidiol) oral solution [prescribing information]. Carlsbad, CA: Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=8bf27097-4870-43fb-94f0-f3d0871d1eec

43. Syndros® (dronabinol) oral solution [prescribing information]. Chandler, AZ: Benuvia Therapeutics Inc. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=a7801c70-995d-46a2-91ee-141ef427c6b5

44. Marinol® (dronabinol) capsules, for oral use [prescribing information]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=d0efeeec-640d-43c3-8f0a-d31324a11c68

45. Cesamet® (nabilone) capsules [prescribing information]. Bridgewater, NJ: Bausch Health US LLC. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=83c7ac15-ece9-47de-b83c-d575544fa449

46. IBM Micromedex® DRUGDEX® (electronic version). IBM Watson Health. Sep 1, 2022. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/

47. Balachandran P, Elsohly M, Hill KP. Cannabidiol Interactions with Medications, Illicit Substances, and Alcohol: a Comprehensive Review. J Gen Intern Med. Jul 2021;36(7):2074-2084. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06504-8

48. US Food and Drug Administration. Cannabis and Cannabis-Derived Compounds: Quality Considerations for Clinical Research Guidance for Industry. 2020. Accessed Feb 9, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/media/140319/download

49. National Institutes of Health. Cannabis (Marijuana) and Cannabinoids: What You Need To Know. Updated November 2019. 2019. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/cannabis-marijuana-and-cannabinoids-what-you-need-to-know

50. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. (2016) Botanical Drug Development Guidance for Industry. Accessed Feb 9, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/media/93113/download

51. Benedict K, Thompson GR, 3rd, Jackson BR. Cannabis Use and Fungal Infections in a Commercially Insured Population, United States, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis. Jun 2020;26(6):1308-1310. doi:10.3201/eid2606.191570

52. Benjie C. Candid Chronicle. Updated Jan 7, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://candidchronicle.com/olcc-recalls-contaminated-cannabis-products

53. Complaints filed about mold in marijuana gummies with 1 sick; recall underway. Food Safety News. Updated Feb 2 2021. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2021/02/at-least-10-sick-from-marijuana-gummies-recall-underway-for-mold-contamination

54. Blake A. Marijuana recall sparked by concerns worker licked pre-rolled cigarettes sold throughout Michigan. The Washington Times. Updated Aug 7, 2020. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2020/aug/7/marijuana-recall-sparked-by-concerns-worker-licked

55. Denwalt D. Marijuana Products Recalled in Oklahoma After Samples Found With Salmonella, E. coli. The Oklahoman. Updated May 24, 2022. Accessed Oct 19, 2022. https://www.oklahoman.com/story/business/2022/05/24/oklahoma-marijuana-products-recall-e-coli-salmonella-mold-cannabis-medical/9906605002/

56. Gill LL. CBD May Be Legal, But Is It Safe? Consumer Reports. Updated Apr 15, 2019. Accessed May 5, 2019, https://www.consumerreports.org/cbd/cbd-may-be-legal-but-is-it-safe

57. Higgins J. Michigan recalls marijuana contaminated by dangerous fungicide. United Press International. Updated Jan 13, 2020. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://www.upi.com/Top_News/US/2020/01/13/Michigan-recalls-marijuana-contaminated-by-dangerous-fungicide/7401578956434

58. Mitchell T. Medical Marijuana from LivWell, WTJ MMJJ Flagged Over Mold Concerns. Westword. Updated Oct 13, 2022. Accessed Oct 19, 2022. https://www.westword.com/marijuana/colorado-medical-marijuana-livwell-colorado-springs-grower-flagged-mold-15223106

59. Denver Department of Public Health & Environment. Cannabis Consumer Protection. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://www.denvergov.org/content/denvergov/en/environmental-health/our-divisions/public-health-investigations/MJConsumerProtection.html

60. Bonn-Miller MO, Loflin MJE, Thomas BF, Marcu JP, Hyke T, Vandrey R. Labeling Accuracy of Cannabidiol Extracts Sold Online. JAMA. Nov 7 2017;318(17):1708-1709. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.11909

61. Vandrey R, Raber JC, Raber ME, Douglass B, Miller C, Bonn-Miller MO. Cannabinoid Dose and Label Accuracy in Edible Medical Cannabis Products. JAMA. Jun 23-30 2015;313(24):2491-3. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.6613

62. Johnson E, Kilgore M, Babalonis S. Cannabidiol (CBD) product contamination: Quantitative analysis of Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol (Delta(9)-THC) concentrations found in commercially available CBD products. Drug Alcohol Depend. Aug 1 2022;237:109522. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109522

63. Sideris A, Khan F, Boltunova A, Cuff G, Gharibo C, Doan LV. New York Physicians’ Perspectives and Knowledge of the State Medical Marijuana Program. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2018;3(1):74-84. doi:10.1089/can.2017.0046

64. Szaflarski M, McGoldrick P, Currens L, et al. Attitudes and knowledge about cannabis and cannabis-based therapies among US neurologists, nurses, and pharmacists. Epilepsy Behav. Aug 2020;109:107102. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107102

65. American Academy of Family Physicians. Marijuana and Cannabinoids: Health, Research and Regulatory Considerations (Position Paper). Updated Jul. 2019. Accessed Jul 17, 2023. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/marijuana-position-paper.html

66. American Academy of Neurology. AAN POSITION: USE OF MEDICAL CANNABIS FOR NEUROLOGIC DISORDERS. Updated Sept 9, 2020. 2014. Accessed Jul 7, 2023. https://www.aan.com/policy-and-guidelines/policy/position-statements/medical-cannabis/

67. American Society of Addiction Medicine. Public Policy Statement on Cannabis. Updated Oct 10, 2020. 2020. Accessed Jul 17, 2023. https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/public-policy-statements/2020-public-policy-statement-on-cannabis.pdf

68. Committee on Substance Abuse CoA, Committee on Substance Abuse Committee on A. The impact of marijuana policies on youth: clinical, research, and legal update. Pediatrics. Mar 2015;135(3):584-7. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-4146

69. American Psychiatric Association. Position Statement Against the Use of Cannabis for PTSD. Updated Jul 2019. 2019. Accessed Jul 17, 2013. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/About-APA/Organization-Documents-Policies/Policies/Position-Cannabis-for-PTSD.pdf

70. Alzheimer’s Association. Cannabis and Cannabis-Derived Products. Updated Feb 2020. 2020. Accessed Jul 17, 2023. https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/Cannabis-and-Cannabis-Derived-Products-Statement-UPDATED-Feb-2020.pdf

Become a member.

See how medical professionals and societies can join the conversation.